The Celtic Zen Map

Zen is a word borrowed from Japanese and means meditation. In addition to zazen (sitting meditation) and kinhin (walking meditation), Celtic Zen also practices meditation techniques from other Buddhist traditions, as well as Druidism, shamanism and Christianity. The system of meditation forms serves the development of wisdom and compassion, healing, the increase of life energy and the experience of transcendence. The different religions define the ultimate goal differently; in Buddhism it is enlightenment or awakening, in Christianity perfection and holiness, and in Druidism more world-facing wholeness.

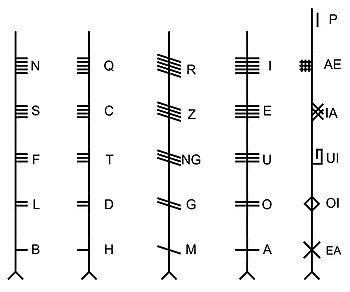

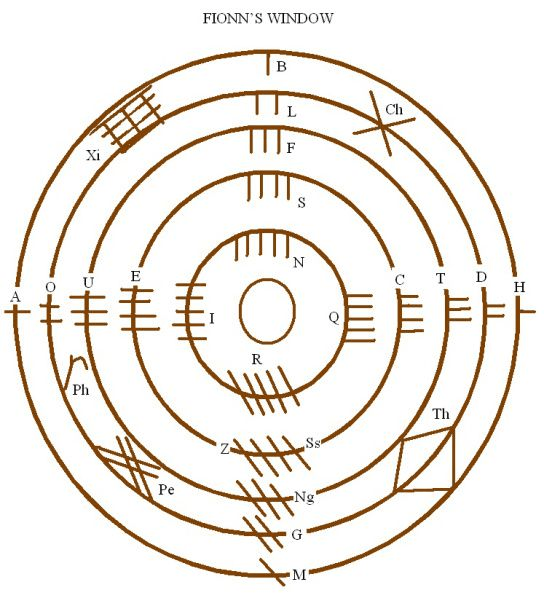

In Zen Druidry we use the Ogham alphabet and Fionn's window based on it to structure and group meditation techniques. The Ogham or (Old Irish) Ogam script (Irish) was used in Ireland and some western parts of Britain or Scotland, mainly from the 5th to the 7th century, to inscribe short texts, in most cases personal names, on the edges of Ogham stones or on other support material. The Ogham script originally consisted of 20 characters called feda (singular fid) in Old Irish. These 20 characters were grouped into four character families, called aicmi (singular aicme) in Old Irish, of five characters each. In the centuries after the peak of Ogham use, various additional characters, called forfeda (singular forfid) in Old Irish, were added.

Fionn's Window, sometimes called Fionn's Shield, is named after the Irish hero Fionn Mac Cumhaill, who was a warrior chief and druid.

Fionn's window consists of five concentric circles on which the Ogham signs are plotted ascending from the outside to the inside in the four Feda groups. The first group is at the top at 12 o'clock or in the north, the second group in the east, the third in the south and the fourth in the west. The added Forfeda signs are on the second outer circle between the main directions.

In Celtic Zen, we assign the Buddhist mindfulness meditations to the four Ogham character groups of the cardinal directions. The division into four corresponds to the division in the basic Buddhist texts on mindfulness, the Anapanasati Sutta and the Sattipathana Sutta. The four foundations of mindfulness are the body, the feelings, the mind and the dhammas. The Anapanasati Sutta describes a path of practice consisting of 16 stages, four for each area of mindfulness. These four-by-four practices are represented by the first four characters of the Ogham character groups. The fifth character (five strokes) represents the area of mindfulness from the Satipatthana Sutta and symbolises the completion of this sequence of exercises. Walking meditation (kinhin) and body meditation are meditation in movement and can refer to all areas of mindfulness.

The four main feda (feathers) of the shield are associated with the solstices and equinoxes, the other four Ogham symbols with the fire festivals. In this way you can use the Dharma Druidry Map as a training schedule in order to learn all meditation techniques in one year. After that you can continue to reconnect and focus on these groups of meditation in order to deepen the experience over time in a structured manner.

The 16 Exercises of Anapanasati

The Anapanasati unfolds breath meditation as a mindfulness path to enlightenment. Beginning with the awareness of the breath in body contemplation, the stages of Concentration (Sanskrit: Dhyana, Pali: Jhana) unfold in feeling contemplation. Concentration is further deepened in consciousness contemplation. In the mind-object contemplation, one recognises the essence of the appearances as empty and releases the attachments to them. Extinction, letting go, detachment are qualities of liberation and awakening.

The Body View - kāya (Ogham Letters B, L, F, S, N in the North, Winter Solstice)

1.“ Breathing in long he knows (pajanati) ‘I am breathing in long.’ Breathing in short he knows ‘I am breathing in short.’

2. Breathing out long he knows ‘I am breathing out long.’ Breathing out short he knows ‘I am breathing out short.’

3. He trains himself ‘breathing in, I experience the whole body.’(sabbakāya). ‘breathing out, I experience the whole body.’

4. He trains himself, ‘breathing in, I calm the bodily formation.’ ‘breathing out, I calm the bodily formation.’ (kāya-saṃskāra)

The Emotional View - vedanā (Ogham Letters H, D, T, C, Q in the East, Spring Equinox)

5. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in experiencing joy.’ (pīti, rapture) He trains himself, ‘I will breath out experiencing joy.’

6. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in experiencing pleasure (sukha, bliss). He trains himself, ‘I will breath out experiencing pleasure.

7. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in experiencing mental formation.’ (citta-saṃskāra) He trains himself, ‘I will breath out experiencing mental formation.’

8. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in calming the mental formation.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breath out calming the mental formation.’

The Consciousness View - citta (Ogham Letters M, G, Ng, S, R in the South, Summer Solstice)

9. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in experiencing the mind.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breath out experiencing the mind.’

10. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in pleasing the mind.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breath out pleasing the mind.’

11. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in concentrating (samādhi) the mind.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breath out concentrating the mind.’

12. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in releasing the mind.’ He trains himself, ‘I will breath out releasing the mind.’

The Mind Object View - dhammā (Ogham Letters A, O, U, E, I in the West, Autumn Equinox)

13. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in observing (anupassi) impermanence.’ (anicca) He trains himself, ‘I will breath out observing impermanence.’

14. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in observing dispassion.’ (virāga) He trains himself, ‘I will breath out observing dispassion.

15. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in observing cessation.’ (nirodha) He trains himself, ‘I will breath out observing cessation.’

16. He trains himself, ‘I will breath in observing relinquishment.’ (paṭinissaggā) He trains himself, ‘I will breath out observing relinquishment.’

The completion levels of the Feda

In addition to the four foundations, the Satipathana Sutta lists other topics that are important for the spiritual path and the development of mindfulness, e.g. dealing with obstacles, meditation of the bodies, the elements, death and others. The Sattipathana is thus broader than the Anapanasati.

The zazen practised in Soto Zen is based on the fact that this is already enlightened being and does not strive for any goal other than sitting meditation itself. All processes in the mind, the body and the environment are consciously perceived. There is nothing else to do or to achieve; which makes the practice complete in itself. The attitude of mind in zazen can be summarised in the three terms shikantaza, mushotoku and hishiryo. Shikantaza (shikan means "only", "simply" or "merely", ta has reinforcing function and za is the "sitting") is usually translated as " just sitting". Mushotoku in Japanese means "not wanting to attain anything, not having a goal". Hishiryo is a state of mind beyond thinking and non-thinking.

In Tibetan Dzogchen, literally the Great Perfection (Completion), it is assumed that all beings possess Buddha nature. There is nothing to attain. The primordial ground of all experience is pure from the beginning. In Dzogchen, the subject itself is the object of contemplation. With questions like "Who am I?", "Who are you?" or "Who is the perceiver?" the practitioner realises not only the emptiness of things but also of the self. In the attitude of pure awareness, all appearances of object and subject are recognised as pure and empty from the beginning and are liberated. It cuts through all illusions and leads to liberation.

The Meditations of the Forfeda

Koad (Hain, Ch, Imbolc)

Koad means grove, i.e. a group of trees, and deals with practices related to community. Some important meditation practice in Druidism is the Sacred Grove. In Christianity there are similar practices called Inner Sanctuary and in Buddhism Inner Refuge. The community relates not only to people, but also to the plants and animals. The development of the eco-self therefore falls into this group. Communal ritual, chanting and dancing are also practices that are often done in community.

Oir (Spindle, Th, Beltane)

The term Brahma Vihara means divine abiding and refers to the development of loving kindness, compassion, co-joy and equanimity. Metta Bhavana meditation is for the development of kindness and charity. Tonglen (giving-taking) is a Tibetan form of meditation for dealing with suffering. Meditation on the Druidic Peace Prayer is for the development of inner peace and equanimity.

Uilleand (Honeysuckle, P, Lughnasadh)

Under this Ogham letter we group the practices that work with energies and visualisations, e.g. tree meditation, light body practice, visualisations, energy centres (chakras) and tantric practices.

In the Nemetona practice, the Celtic goddess of the sacred groves and tribal goddess is visualised and mantras are recited. She enters one's own body as a ball of light. Object and subject merge and unity emerges. With the dissolution of the fused ball of light, a consciousness arises in which all phenomena can be perceived without clouding of the ego. Link

Phagos (Beech, Ph, Lughnasad)

The beech symbolises the written word and the transmission of ancient knowledge. Lectio Divina is a scriptural meditation that originated in the Benedictine tradition. This can also use nature as a basis. One-word prayer or mantra prayer is not only a form of prayer, but also a way into contemplation. In Rinzai Zen, the reflection of koans is used to overcome rational thinking and to gain answers to paradoxical questions through intuition. Parallels to this can be found in the triads of Druidism and in the logia of the Gospel of Thomas.

Mor or Amhancholl (Sea or Witch Hazel, X or Ae, Samhain)

The word Mor stands for the sea and the ocean and symbolises change and the journey. This includes the exercises with shamanic journeys, soul retrieval and pilgrimage, whether external or internal.